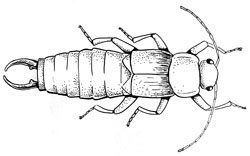

James Joyce would have approved of Lucy Cooke’s attempt to rehab the image of the sloth. A zoologist and founder of the Sloth Appreciation Society, Cooke argues that sloths get a bad rap. This unusual mammal—the world’s only “inverted quadruped”—derives its name from one of the seven deadly sins—“sloth”—a failing that’s drawn censure throughout history from moralizers as various as puritans, businessmen, physicians, and gym teachers. Scientists have recently speculated that pygmy sloths in Panama spend much of their lives stoned on Xanax (actually, benzodiazepine-like compounds in fungus associated with red mangrove leaves), which doesn’t improve their reputation. But don’t be fooled, Cooke says in her fun and funny book, The Truth About Animals. The sloth’s lassitude is in fact a canny survival tactic, a byproduct of its low-calorie diet, correspondingly low metabolism and body temperature, and its need to hide from the constant menace of harpy eagles. In other words, for these two- and three-toed folivores in the rainforests of Central and South America, sloth is a Darwinian virtue, not a sin.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again, no matter how many times my Aunt Betsy and very few others have heard me say it: Joyce is the modern master of just this sort of rhetorical ju-jitsu, which grapples medieval definitions of vice and virtue, flips and pins them down in new positions of honor or shame. It all started in Dubliners, systematized around the seven deadly sins and the Christian virtues, each of which Joyce interprets in a way that would give a priest shpilkes. The sin of sloth becomes a virtue in the eleventh story in the collection, entitled “A Painful Case.” Like Finnegans Wake, whose celebration of sloth I will analyze in a moment, “A Painful Case” takes place in the western suburb of Dublin called Chapelizod. This is where aging bachelor and bank cashier James Duffy lives and where he tragically illustrates the value of slowing down by utterly failing to do it. He almost manages to unwind into a love affair, but it doesn’t come easily to him. Duffy’s as industrious and ordered as a clock.

“Mr Duffy abhorred anything which betokened mental or physical disorder,” Joyce writes. “He lived at a little distance from his body, regarding his own acts with doubtful side-glances.” (Dubliners, Viking ed. p. 108) “His liking for Mozart’s music brought him sometimes to an opera or a concert: these were the only dissipations of his life.” (p. 109)

It’s at one such musical performance that Duffy meets Emily Sinico, a 43-year-old unhappily married to a neglectful ship captain. Just when their intimacy is about to take the next step, however, Duffy abruptly breaks it off. “[H]e bade her goodbye quickly and left her.” Then: “Mr Duffy returned to his even way of life. His room still bore witness of the orderliness of his mind.” (p. 112) He hurries past the only meaningful affair in his adult life in order to resume the ordered rhythm of duty and commerce. Years later, he learns from a newspaper that Emily became an alcoholic and died in a traffic accident. Duffy blames himself. It’s a tale of star-crossed lovers like Tristan and Iseult. (The “Izod” part of “Chapelizod” derives from the name of that unhappy Irish princess.) In the end, he wanders cold, alone, and unwanted before the gaze of two lovers lying together by the Phoenix Park wall. If only he’d been able to let himself slow down, if only he’d been willing to lie down like the Phoenix Park lovers and detach for a while from the moralistic world of duty and schedule, he might have been happy.

Finnegans Wake is in a sense a literary temple Joyce constructed on the site of Mr. Duffy’s failure at Phoenix Park. The Wake invests slowing down, sloth, sleep, relaxation, unconsciousness, and rest with a quasi-religious significance, honoring these bohemian, anti-bourgeois, impious values not only by granting them all the real estate in the book, but by fulfilling at last Stephen Dedalus’s absinthe-soaked pledge to destroy Death and Time in Ulysses. In Bella’s Nighttown brothel, Stephen cries out to the ghost of his dead mother and her ring of phantasms, “Break my spirit, all of you, if you can! I’ll bring you all to heel!” Then he drunkenly attacks a chandelier with an ashplant cane. It’s a symbolic demolition of Time itself via odd stage-directions that disobey the rules of Time: “Time’s livid final flame leaps and, in the following darkness, ruin of all space, shattered glass and toppling masonry.” (Gabler ed. 475.4244-5) Like everything else that happens in a brothel, it may sound good but it doesn’t achieve the end.

The Wake’s timeless, circular riverrun and unhurried satire achieve the end more subtly and successfully. It spends vast tracts in parody of Earwicker’s son Shaun, a “gogetter that’d make it pay like cash registers” (451.4-5), a conventional bourgeois buffoon and figurehead for productivity, piety, and earning potential* whose bodily appetites make a fool of him, causing him to gobble food uncontrollably in the middle of his own grandiose sermons. Through satire, Joyce divests himself of Shaun and his namesake James Duffy and casts them off like former selves for which he no longer has any use. Shaun’s brother Shem, an artist, slob, and hermit, comes in for satire too—Joyce was too guilty about his bohemian laziness, perhaps, not to self-flagellate for it—but it’s quite clear Shem’s the protagonist, not Shaun who, in a parody of the Fall of Man like Tom Kernan’s drunken tumble down the stairs in “Grace,” completes his sermon and immediately collapses backwards into a barrel and is washed away in the Liffey.

Despite the guilt of napping and the anxieties of dreams, The Wake succeeds in honoring sleep as a reprieve from “noondayterrorised” consciousness. (184.8) We sloths aren’t sinners! We’re merely seeking respite from the harpies, whose talionic code would deny us the idle and uncounted hours reserved for love and art.

*For his 17 years of labor on this last masterpiece, Joyce earned an advance from Viking of just £700.