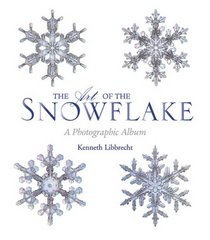

Professor Libbrecht has braved many a winter day in the frozen countrysides of Wisconsin and Alaska and elsewhere, harvesting snowflakes on glass slides and photographing them under the microscope in what he describes as an unusual hobby. He also studies crystal formation professionally and explains quite clearly how snowflakes form, how the geometry of H2O predestines their hexagonal structure, what rime and graupel are (sounds like two sisters in a Grimm’s fairy tale or ingredients in a cardboard-tasting high-fiber cereal, but no), how the stochastic intercourse of humidity and temperature and wind create a unique life-history for each falling snowflake, which records that history in its physical form–rounding off when falling through a warm patch of air, for example, then continuing to accumulate more or less ice on its prominent corners in a cold zone to acquire a stellar shape.

Libbrecht quotes from William Matthews (who is he?): “And here comes the snow, a language in which no word is ever repeated.” Sometimes the simplest things, those facts acquired in the wide-eyed days of elementary school, are still the most stirring to the soul: every snowflake different from all those that ever have been or ever will be! Jorge Luis Borges had nightmares about a machine that could generate all combinations and permutations of letters in an alphabet, thereby creating every work of literature that ever has been and ever will be. But if you do the math, the number of combinations and permutations of even one page of letters of the Roman alphabet is of an order of magnitude larger than those that describe the size and age of the visible universe! Infinitude can be terrifying in its incomprehensibility when one feels down, and finitude can be equally terrifying and incomprehensible, and yet doesn’t the snowflake reflect something wonderful and human? That the ephemeral form is not without significance, being the one and only record of existence at particular coordinates in time and space, a beauty rendered from the heavens with careless ostentation, beauty that can be seen like airborne diamond dust, tasted on the tongue like a mint leaf, or sledded on.

Read this book alongside the poems of winter bard Robert Frost and go skiing or snowshoeing through woods “lovely dark and deep” and remember that a poem like ice must “ride on its own melting.” Sometimes it must be enough to look at the universe and say, ‘Though my understanding is incomplete I know this: that it is good.’ Or at least, ‘Just because I don’t understand it all, I know not why it should be bad.’

Personal quirk: I find snowflakes of the double-plated variety and snowflakes that are “capped columns” disgusting and always did, even when I was a kid and examined them on the sleeve of my winter coat. Yet the clouds apparently keep making them. (They do look better under a microscope, however.)