Rest in Peace. The phrase itself is a “dead metaphor”—so old and familiar, we no longer see it as metaphor at all. Rather, we see it as lamentable news of the most concrete, unvarnished fact of life: a death. But its root components in fact originate in an ancient metaphor, a comparison between sleep and death found everywhere from Homer and the Hebrew Bible to Shakespeare and Sleeping Beauty. And it’s the metaphor that undergirds the whole of Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, which uses images of night and sleep to parody death. Shem the Penman, in his guise as schoolboy Dolph, plays at such parody in the chapter known as “Night Lessons.” Having digressed for a while about a dead mother*, Shem turns back to his former subject with a farewell “Rest in peace!” His next words signal his intention to resume where he left off before digressing: “But to return.” This is also a pun, however, that completely undoes the woebegone acceptance of death in the previous line: “Rest in peace! But to return.” (295.15) The satirical pen of James Joyce: where dead metaphors come back to life.

Ancient writers employed the sleep-death metaphor poetically and beautifully, but never satirically. In his 1933 paper “The Sleep of Death,” Marbury B. Ogle*, one-time classicist at the University of Minnesota, collates instances of the metaphor from across ancient literature, including a lovely pair from Homer and Virgil. In The Iliad, Agamemnon ferociously strips brave, young Iphídamas of his sword and cuts his throat with it. Homer writes of the Thracian boy, “Down he dropped into the sleep of bronze.” (Fitzgerald trans., p. 258) With mention of sleep, Homer skillfully tempts the reader with the hope that Iphídamas isn’t dead but just asleep, then swiftly turns the wish to unfeeling, unyielding bronze, doomed to sink into the cold and dark. Centuries later, Virgil applies this exact Homeric sleep-death / wish-reality formula to the death scene of Trojan warrior Orodës: “Harsh repose oppressed his eyes, a sleep / Of iron, and in eternal night they closed.” (Aeneid, Fitzgerald trans., p. 321)

The graveyard epitaph “Rest in Peace,” meanwhile, seems to have originated with the ancient Hebrews. (E.L. Doctorow’s young protagonist in World’s Fair has “the distinct impression that death was Jewish” for good reason.) The phrase “rest in peace” occurs all over the Bible in various forms and in the still-current Jewish funeral prayer Kel Maleh Rachamim, which begins by asking of God ham-tzay m’nucha, or “provide rest [to the deceased],” and concludes with the more direct nuach b’shalom, or “rest in peace.”* After speaking the name of a dead person, living Jews of a certain generation sometimes say alav ha-shalom, which has a similar sense of “peace be unto him.” And Jewish tombstones from the Roman Empire bear the inscription dormitio in pace (“sleeping in peace”), according to our friend Marbury Ogle, who is currently dormitio in pace in Lafayette, Indiana, unless someone has been digging up Midwestern classics professors.

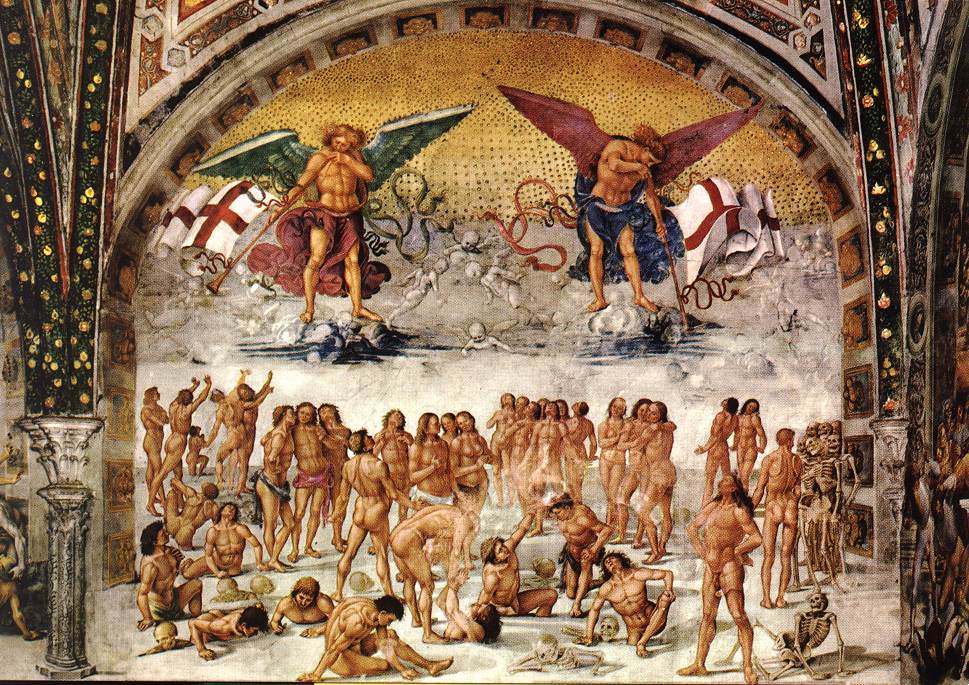

The Jewish prayer seems to turn the sleep-death metaphor in the direction of euphemism with a hope of resurrection; if death is only sleep, then the dead can wake up. Ogle notes this tendency among Greek philosophers, too: “The comparison of death to sleep evidently became a commonplace in the discussions of philosophers concerning the nature of death and in their arguments to combat the fear of it.” The Hebrew Bible repeatedly invokes the language of awaking from sleep to describe actual resurrections. The Book of Isaiah 26:19, for example, says: “Thy dead men shall live, together with my dead body shall they arise. Awake and sing*, ye that dwell in dust: for thy dew is as the dew of herbs, and the earth shall cast out the dead.” The Christian Gospels never directly depict Lazarus or Jesus “awaking” but Christian tombstones do say “rest in peace,” updating dormitio in pace to requiescat in pace and R.I.P.

As one might expect, James Joyce has a more blasphemous take on the metaphor. He comes to it through the raucous Irish ballad “Finnegan’s Wake” in which whiskey-loving hod-carrier Tim Finnegan falls drunk from a ladder and dies. Tim’s “laid out on the bed / With a bottle of whiskey at his feet / And a bottle of porter at his head.” Friends and relatives get drunk and fight over his open casket and accidentally christen his body with spilled whiskey. Tim leaps from his casket and cries, “Thanam an dhoul [Gaelic curse: your soul to the devil], d’ye think I’m dead?” Joyce echoes the ballad’s events in the first chapter of Finnegans Wake with funny, drunken corruptions of the lyrics like “Anam muck an dhoul! Did ye drink me doornail?” (24.15)

Both song and book use the ancient sleep-death, waking-resurrection metaphor less to romanticize death than to give it the finger, rebelling against neurotic conscience and despair through satire and laughter. In all of Joyce’s work, he mimics the religious language of guilt and uses it to say something life-embracing: in Dubliners, he turns deadly sins into earthy virtues; in Finnegans Wake, he takes his satirical rapier to death itself, refusing to identify with death despite conscience’s demand that he should. Instead he satirizes death as a long drunken sleep with morning—not mourning—at the end of it. A funeral in this way becomes “a grand funferall” (13.15), and a cemetery no more than a “seemetery.” (17.36) The Wake itself refuses to die. It doesn’t even have an ending, but instead concludes in the middle of a sentence that resumes in the novel’s first line:

riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.

<text of Finnegans Wake>

A way a lone a last a loved a long the

* In the spirit of ending in the middle, a few miscellaneous notes. 1) Dead mothers are a major theme for Joyce, who lost his when he was 21. Ulysses commences with abundant references to a mother’s death and Finnegans Wake concludes with a heart-wrenching mother of a mother’s death scene. 2) Marbury B. Ogle seems to have had a relative named Ogle Marbury who was long ago chief justice of the Maryland state supreme court. Also, Marbury O. married his wife Anetta on June 14, 1904, exactly 2 days before Joyce’s first date with Nora Barnacle, being the day on which Ulysses takes place, June 16, 1904, i.e. the original Bloomsday. 3) Nuach in Hebrew means rest in English and also spells the name Noah. The biblical story of Noah, who “giveth rest to the rainbowed,” as Joyce puts it (133.31), constitutes another major theme of Finnegans Wake. 4) Awake and Sing is the title of Clifford Odets’s first play, which debuted in 1935. In a 2006 Lincoln Center production, Mark Ruffalo played the rumpled yet dashing Moe, and before the celebrity-adoring audience was done applauding his entrance, he said coolly to the young women onstage: “Hello girls! How’s your whiskers?”