Last March, an archaeological survey in Japan turned up a 16-inch unexploded artillery shell near a bullet train track in north Tokyo. The trains were stopped in early June so the Japanese army could dispose of it. Such incidents are normal in post-war Japan; tons of unexploded ordnance are discovered and removed every year there and it’s estimated that thousands more tons remain buried in the ground, like bad memories that may be suppressed, but don’t go away. The problem seems emblematic of Japan’s struggle to digest painful history—not only the recent calamity of World War II, but centuries of earthquakes, tsunamis, and apocalyptic civil wars.

The consciousness of calamity has informed Japanese art since ancient times. Columbia University Press’s Sources of Japanese Tradition, edited by Ryusaku Tsunoda, Wm. Theodore de Bary, and Donald Keene, tells us of the ancient state records called the Nihongi or Chronicles of Japan: “Over and over in the Chronicles of Japan we find such entries as the following (for A.D. 599): ‘There was an earthquake which destroyed all the houses. So orders were given to sacrifice to the God of Earthquakes.’ ” (Tsunoda p. 267) Buddhism and Chinese philosophy came to Japan around the same time as the earthquake mentioned above, and both found favor in the island nation, perhaps because they squared so well with the old Shinto fear of nature. Buddhism expresses a deep sense of the changeability and impermanence of the natural world and a determination to reach some inner, mental accord with it (Tsunoda, p. 96). The Chinese school of yin-yang provided to Japan the art of “avoiding calamities” by divination. (Tsunoda, pp. 58-59)

An acute sense of perishability and calamity remains in the Japanese art of modern times—having been reinforced no doubt by the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the torrent of conventional ordnance that the U.S. air force rained on Japan during World War II. (Some Japanese referred to the bloody sea and air assault on Okinawa as the “Typhoon of Steel.”) Japanese disaster films like Godzilla and the Japanese-influenced Pacific Rim of last summer bespeak the preoccupation with calamity, as does Japanese contemporary high literature. Yasunari Kawabata, who in 1968 became the first of two Japanese Nobel laureates in literature, worked directly in the calamity tradition. Much as W.G. Sebald did in Germany, Kawabata wrote characters whose inner lives were contaminated with the unexploded ordnance of the past.

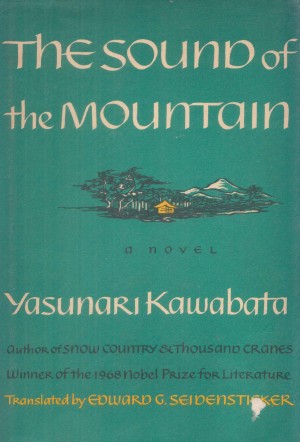

Kawabata’s The Sound of the Mountain was first published in 1954, and while his characters for the most part avoid talking about the war, the scars and holes that war left in Japanese families play a dominant role in their lives. It’s a story of veterans, widows, and orphans, of a Japan where “[a] great many children were left behind by men who died in the war, and a great many mothers were left to suffer” (The Sound of the Mountain, p. 233)—a story where, as war veteran Shuichi says, “[the war] is still haunting people like me. Still somewhere inside us.” (p. 266) Encyclopedia Brittanica says of Kawabata, who was born in 1899, “he was orphaned early and lost all near relatives while still in his youth” and from the outset of the novel we gather that if life is short and fragile, calamity’s influence on the human mind is long and enduring. Here is the protagonist Shingo arguing with his wife Yasuko about their troubled granddaughter Satoko (if you think those names are confusing to a Western ear, the family also includes a Fusako, a Kuniko, and a Kikuko—thank God for Shuichi):

“She was born after things started going bad with her father,” said Shingo. “It all happened after Satoko was born, and it had an effect on her.” “Would a four-year-old child understand?” “She would indeed. And it would influence her.” “I think she was born the way she is.” The Sound of the Mountain p. 23

The dark weather of past times perhaps does something to corrupt the mind so that it makes its own storms, as Shingo observes later:

“Even when natural weather is good, human weather is bad,” he muttered to himself, somewhat inanely. The Sound of the Mountain p. 185

The “somewhat inanely” tacked onto the thought is a case-in-point. Shingo’s mind distorts its picture of itself and makes bad weather out of good, for the statement is not inane. It’s profound. The calamities of war and lost love have corrupted his thinking:

Women had left his life during the war, and had been absent since. He was not very old, but that was how it was with him. What had been killed by the war had not come to life again. It seemed too that his way of thinking was as the war had left it, pushed into a narrow kind of common sense. The Sound of the Mountain p. 210

The “narrow kind of common sense” seems to be an “art of avoiding calamities” that extinguishes desire and the will to live by too many “pious thoughts about the dead” (p. 219). People in this novel, as in real life, find ways to imagine that they’re responsible for the calamities that befall others. Just as ancient Japanese authorities concocted a magical art of avoiding calamities by making sacrifices, the characters in The Sound of the Mountain seem to sacrifice themselves on the magical altar of abortion and suicide, as if that would undo the calamities that have befallen others. So Kikuko does not put up a fight when her husband Shuichi has an affair with a war widow and impregnates her. Instead she aborts her own pregnancy: the art of avoiding calamity gone all awry.

Kawabata himself committed suicide in 1972, but he had written against suicide: “However alienated one may be from the world, suicide is not a form of enlightenment.” It appears Kawabata fought with demons, as his characters do in The Sound of the Mountain. And before he lost one of those battles, he won a great many of them, and his weapon in the fight was his art, a beautifully modern update to the ancient calamity art of Japan.

The Sound of the Mountain combines realistic dialogue and depth psychology with aware, a trope associated with The Tale of Genji, which some consider the world’s first novel; it was written around 1010 C.E. by Lady Murasaki Shikibu. Sources of Japanese Tradition explains aware like this: “It bespoke the sensitive poet’s awareness of a sight or sound, of its beauty and its perishability.” (Tsunoda, p. 176) It converts melancholy to joy by seeing the beauty in a transient moment or by beautifying it in poetic language, but also perhaps by penetrating beyond despair to a possibility of joy that may be latent in the transient scene.

The eponymous “sound of the mountain” turns out to be the remembered sound of an avalanche in Shingo’s childhood. Kawabata arrests the frantic movement of an avalanche with his beautiful and meaningful aware, an image of an avalanche that is still and calm and subject to contemplation as in a Japanese painting.

At one point Shingo recalls a real painting by Watanabe Kazan with the legend “A stubborn crow in the dawn: the rains of June.” Shingo remembers the crow “high in a naked tree, bearing up under strong wind and rain … awaiting the dawn.” (p. 209)