Harold Bloom says that Freud learned all his psychology from Shakespeare. Would it be radical to suggest that Shakespeare learned half of his psychology from the Romans and the other half from the Hebrew Bible?

Robert Alter says of the Bible’s authors, “[T]he Hebrew writers manifestly took delight in the artful limning of … lifelike characters and actions, and so they created an unexhausted source of delight for a hundred generations of readers.” The Bible is generally more realist in style and more concerned with the minute details and subtle intricacies of mental life than say, Homeric epic, or the plays of Aeschylus, where emotions certainly occupy a central position but are seen at a longer psychic distance and are represented in more abstract ways.

When Cain is snubbed by God, who heeds Abel’s offering but not the older brother’s, I can put myself in Cain’s shoes (sandals) more readily than I can in those of say, Menelaus, after Paris absconds with his wife. I understand Menelaus on a more intellectual level. When Cain is snubbed, the Bible says “his face fell” and that God asked him, “Why is your face fallen?” The narration and the figures in the stories themselves are remarkably attendant to the inner life, to discrepancies between the outward manifestations of thought and feeling and the inner facts, to discrepancies between intention and action, even between inner ideas and deeper levels of consciousness (i.e., the Bible depicts lies told to oneself; i.e., denial ain’t just the river where Moses turned up in an ark of bulrushes). Noah’s ostracism of his son and grandson and Sarah’s jealousy of Hagar are entirely modern-feeling accounts of guilt and jealousy and the way such emotions are handled in the psyche.

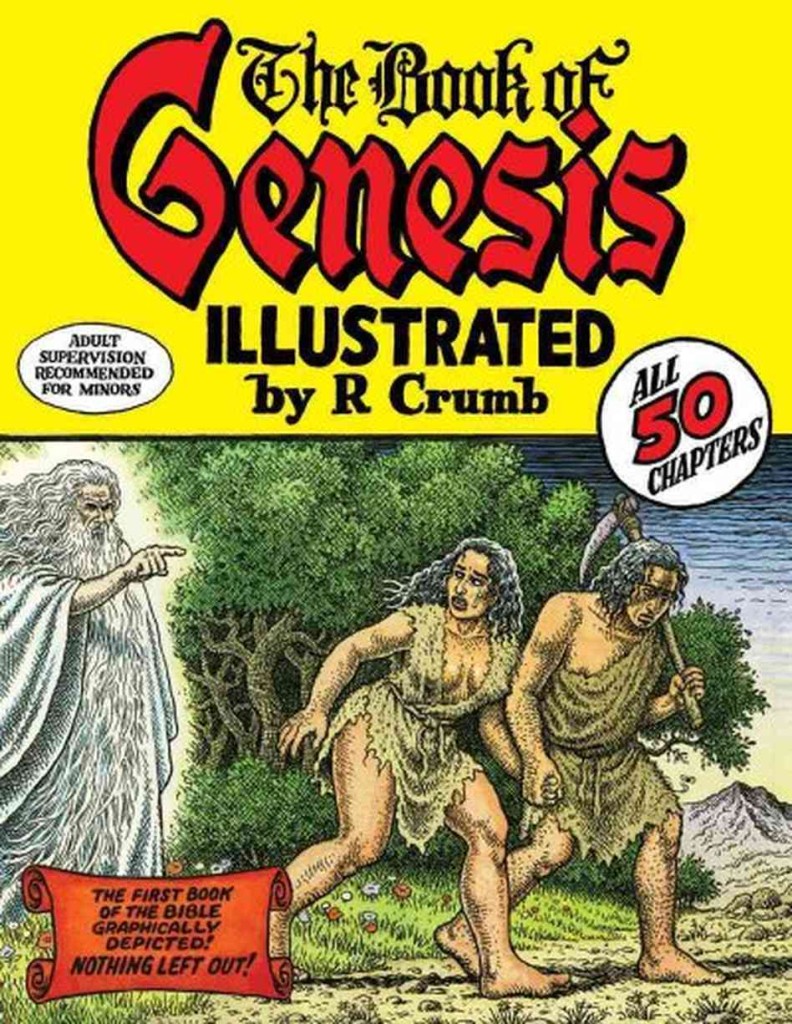

R. Crumb’s recently published illustrations of the Book of Genesis amplify this psychological pathos in a wonderful way without diminishing the Bible’s subtlety. Crumb shows Cain sweating under the weight of his offering to God juxtaposed with the tiny lightweight lamb that Abel brings. You see how unfair and hurtful it was for Cain and understand what came next.

Some of the Crumb illustrations are funny and implicitly ask subversive questions about God, particularly in the earlier chapters, where God enters the story as a kind of lunatic artisan who likes to make things for reasons unknown to anyone, including, apparently, himself and who gets furiously dissatisfied with his creations and takes out all his frustrations on his children like the put-upon alcoholic Farrington in James Joyce’s story “Counterparts.” The things God yells about seem not to make any sense as in a real human temper tantrum. The opening passages of Genesis may lose some of their gravitas in this version, but the familial dysfunction at the heart of so many of the Bible stories is thrown into bold relief. Furthermore, the satire in these early parts lends a certain existential irony to the stories, which I appreciate, and which it might be argued is not even foreign to the biblical writers. Alter sees the Bible’s main agenda as the depiction of human character in all its variety and consistency, and that character’s interrelation with forces beyond human control—fate, destiny, chance (or God, if you prefer)—to create what we call history. Sometimes the biblical heroes themselves don’t understand God’s designs, and sometimes laughter is the result, as when Sarah laughs at God’s annunciation of her pregnancy in old age and this laughter is commemorated in Isaac’s name, which means “he who laughs.” Sometimes the heroes object to God’s designs, as when Abraham bargains for Lot’s life. Sometimes God seems like a personification of the sort of natural disaster that just befell Haiti as when God wantonly destroys Babel. It might be argued that the biblical writers purposely made God at times cruel and outrageous because fate is cruel and outrageous. And inasmuch as the Bible writers rationalized natural disasters as punishments for bad behavior (as Pat Robertson does even today) or otherwise rationalized them as in any way useful or necessary or morally ordained—well, then this benighted and primitive element of their worldview deserves satire.

On the whole, however, what’s so remarkable about the ancient writers of the Bible is not what’s primitive about them, but what is modern. They have honored the complexity and majesty of the real world with the most meticulous artistry and have not only bequeathed their wise and beautiful stories to later readers but their techniques to later writers and artists.

I reread Genesis in Crumb’s illustrated edition (which uses Robert Alter’s translation, a major upgrade from any I’ve read, sensitive as it is the artistic aims of the original Hebrew) and afterward I read Robert Alter’s The Art of Biblical Narrative, a masterpiece of literary criticism and a highly accessible one at that. If you want a pair of excellent guides to one of the great artistic creations in the history of humankind, I commend to you the Roberts Alter and Crumb.

Addendum: On Bloom’s notion that Freud got everything from Shakespeare; this is surely “the anxiety of influence” in action—a wonderful concept Bloom invented with a little help from Freud. (As that immortal rock band The Bettelheims said, “I get by with a little help from my Freud….”)