“Sometimes you are not happy to hear the truth, because it hurts inside,” Georges Perrier, chef of the famous Philadelphia restaurant Le Bec-Fin, told the New York Times upon his retirement. “But I have to accept it.” Perrier retired shortly after a newspaper review skewered the restaurant for a terminal decline in quality.

Impressive, in a way–or is that just the sort of ennui that once caused a Frenchman named Claude to tell me and my dad without a trace of irony, “I am too tired to go on lee-ving….”

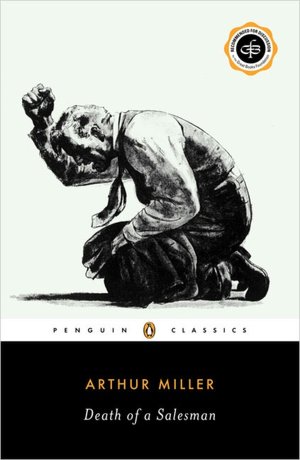

In any case, Perrier’s words would never have arisen in the throat of Willy Loman, the all-time maestro of self-deception. “I don’t want change, I want swiss cheese!” Willy cries out to his wife in Act I. It’s funny out of context, and I think I’ll keep the line out of context as a souvenir, but it also speaks to the forlorn, bewildered, childlike beast that Willy Loman is–he is “a poor, bare, forked animal” with a simple and small desire, the desire of a mouse, in fact, a mere morsel of cheese! But like King Lear, he encounters a world bent upon frustrating even the most miniscule of human desires. His frustration exceeds his humiliation threshold and he seeks a way out in suicidality. His son Biff bears the burden of filial responsibility for his crumbling father, who he once adored, so Miller has his Lear and his Hamlet together in one ringing gong of a play.

Willy cannot feel the obvious, overt love of his sons or his wife, in part because of scarring abandonments in his deep past inflicted by his own father and brother. (A dreamed phantasm of his brother enters and re-enters Willy’s thoughts, boasting of exploits with diamonds in the jungle and the Alaskan wild.) When Willy tells this phantasm that their father left when he was three or four, and asks his big brother for details about their father, the phantasm brother coldly specifies that Willy was three years eleven months when their father left as if the fact has no more meaning than to reflect the sharpness of his memory. He boasts afterward that with all his businesses he doesn’t even keep any books, not noticing the mortal wound in the heart of the man in front of him, and not feeling a bit of fraternal responsibility to him. But the fact concerning their father’s abandonment inspires a rare moment of lucidity and truthfulness in Willy. He seems grateful for this tiny bit of nutrition to his famished spirit, and he says to his brother beseechingly, “I never had a chance to talk to him [their father], and I still feel–kind of temporary about myself.”

When Philip Seymour Hoffman (who was born to play Willy Loman) utters lines like these, you hear people in the Barrymore Theater actually sigh or gasp. By the end, you hear people sniffling all around you. It hurts like broken fingernails to watch Willy Loman setting himself on fire, refusing to be helped, and watching Biff (Andrew Garfield of The Social Network) immolate himself on his father’s pyre. This is a devious shapeshifting rotating slithering demonic viper of a play, come to kill and eat its audience with its bare hands. It’s wrought with bewildering skill, and is in some respects more O’Neill than O’Neill, more Aeschylus than Aeschylus. Arthur Miller done gone Greek on our ass with the pity and the fear.

Mike Nichols’s production, which reproduces the original 1949 set to the molecule, left me bleeding all over my soul from its 100,000 viper bites of despair. (A fun night out at the theater! My wife joked at the intermission, “Well, at least it has a happy ending!” and I said to the woman sitting next to us, “Yeah, don’t worry, I hear it all works out in the second half!”) Hoffman is the master portraitist of self-deceivers, that tortured species which deserves its own private wing of heaven in which to recuperate from life. Hoffman unearths aspects of Willy Loman I’ve never noticed before: that he has charm and wit, and that his crazy volte faces from puffed up aspiration to sudden gloom have an inherently comic rhythm to them. Also, I appreciated that just as when I saw Hoffman on stage next to Robert Sean Leonard in Long Day’s Journey into Night, Hoffman’s head was one and a half to two times as large as Garfield’s.

Even if watching a good production like this is fatal to a melancholic soul like me, I’ll always have a soft spot for this play, if only because I won the Arthur Miller Prize for Fiction at the University of Michigan in 1992 and was given a copy of the play inscribed by the master himself, Arthur Miller. There were no more than 20 or so of these awards ever given. U of M also sent my award-winning juvenalia to Miller and I like to think he at least passed his eyes across the letters of my name.