Dubliners was James Joyce’s first book, and it’s his most accessible, and possibly his most influential. The critic A. Walton Litz called Dubliners “a turning point in the development of English fiction.” Marc Wollaeger, editor of the Oxford Casebook on A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, writes that “Dubliners … virtually invented the modern short story.”

I don’t know if Joyce invented the modern short story, but I can see pretty much everywhere in contemporary fiction the influence of Dubliners, of its Shakespearean / Chekhovian trope of self-discovery affixed with a technique of beautiful naturalistic symbolism–the blend of ancient artistic modes which Joyce called “epiphany.” Joyce’s writing style in Dubliners has more in common with Hemingway than it does with Virginia Woolf or William Faulkner (and Hemingway’s best short stories clearly reflect Joyce’s influence), but the characters in Dubliners are generally somewhat warmer and more vulnerable than Hemingway characters and Joyce depicts men and women with equal grace.

Brewster Ghiselin said in 1956 that the stories are organized according to the seven Christian virtues and the seven deadly sins, with each of the first fourteen stories assigned to a virtue or sin and the fifteenth story, the masterpiece “The Dead,” thrown in for a delicious baker’s dozen of tales of inner torment. I think it’s obvious that Joyce did use that structure, though he turns vice and virtue on its head in the manner of Henrik Ibsen as he attacks the damaging institutions of psychological paralysis and self-mortification.

“The Sisters,” the first story in this collection and the one that formally introduces the topic of psychological paralysis, is my personal favorite, but the two most famous stories, “Araby” and “The Dead,” deserve all the praise they get.

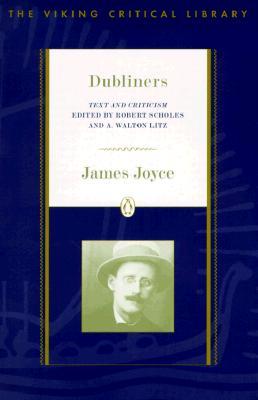

I like the Viking Critical Library edition, at least the one that was published in 1976; the essays in the back are unusually helpful.