By a long shot, this is the funniest book I ever read about the blood libel.

Caveat: despite illustrations by Uri Shulevitz that look suited to children, this is not a children’s book. It’s about some gentiles who libel an innocent Jew for the murder of a child in 17th-century Prague. German folklore, of course, really did depict Jews as demonic figures who used Christian children’s blood in their matzah. The legend is gruesome enough, but its demonization of Jews is even more troubling given the catastrophic consequences of such racism in the real lives of European Jewish families as recently as sixty years ago. Golem folklore, meanwhile, emerged from the Jewish ghettoes of Europe and, at least in Singer’s telling, serves as antidote to the racist folklore known to Jews as the blood libel. Golems are pretend, as are demonic cannibal Jews, as is the arch distinction between heroes and villains in this and other fairy tales. (Singer surely painted the righteousness of the Jewish victims and the venality and mendacity of their gentile accusers in stark terms so that the charges of cannibalism in the story would be understood as unambiguously false.) But it’s important to note that Isaac Bashevis Singer didn’t make up the notion of the blood libel. The blood libel appears in Chaucer’s poetry and in the original edition of Grimm’s fairy tales. In The Golem the judge uses the frequency of the accusation of cannibalism as evidence of its validity. That is surely one of the ways that rumors propagate–people believe hoax emails today for the same reason–and the Jews of Europe, an ostracized minority, were powerless to resist the damage the legend wrought. They dealt with it as the Jews had previously dealt with hardships: they told stories about it.

Part of what makes Singer’s story so funny and unusual is that it shifts from tragedy to comedy half-way through, when the Golem, having solved a major problem for the Jews of Prague, starts acting crazy in a very childlike way, doing unexpected and yet harmless things like climbing the bell tower and running around the bell and kissing a girl (who finds “his lips were as scratchy as a horseradish grinder”). The Golem, an earthen clay giant shaped by a rabbi with the name of God engraved on his forehead, seems to function like a work of art in the life of the Jews–like an Isaac Bashevis Singer story–alleviating tragedy through might and also through comedy. The Golem is the creative life-force of the Jews, called up from the sacred depths of the spirit at their darkest hours with pious intensity, and then blundering past tragedies with actions bent implacably upon the earthly and profane. The Golem doesn’t listen to the rabbi and becomes preoccupied with childish games and the sort of quotidian needs that can look so trivial and absurd in the context of tragedy. And by suggesting absurdities, the Golem performs a magic act like the one that called him into being: he summons laughter out of us like a genie out of a lamp, and our laughter in turn calls us back to the necessity, the joy, and significance of daily life.

One indicator that the Golem does not belong to the Gothic story tradition of self-destruction is his attitude to wine. Boris Karloff as Dracula: “I don’t drink … wine.” Frankenstein’s effete monster too specifically disapproved of wine. The Golem: “Golem like wine!” Even Manischewitz, apparently.

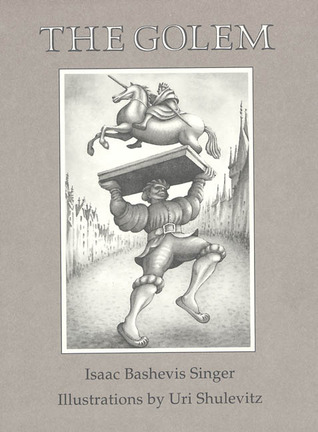

Isaac Bashevis Singer has a master’s intuition and lightness of touch. Uri Shulevitz’s illustrations are perfect: funny, sincere, a little sad, big, and strange.