Roald Dahl is the burrowing fox of children’s literature. His mind burrows deeper and deeper into a story possibility and discovers within it a world of miniature wonders. He takes you on a voyage into mental and physical inner space–inside the labyrinth-like chocolate factory, into the underground tunnels of the fantastic Mr. Fox, inside a giant peach (in James and the Giant Peach) through a tunnel, one notes, that looks to James like a foxhole.

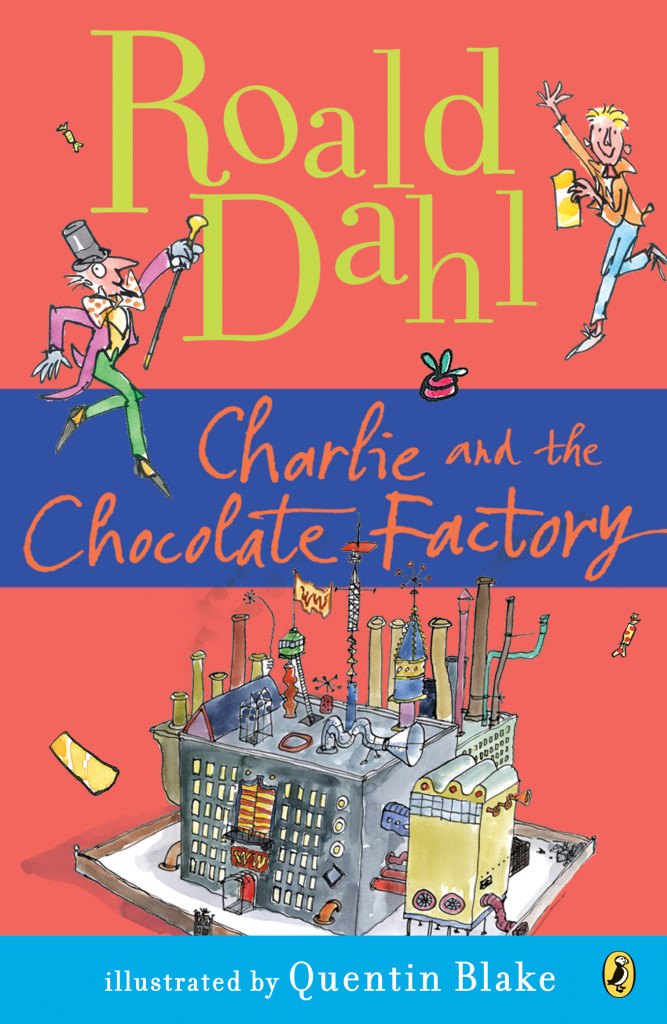

Willy Wonka, the fictional proprietor of the chocolate factory, is like Walt Disney a curious mixture of showman, pied piper, puritan, capitalist, and wish-granting genie–a distinctly Anglo-American figure. The four spoiled children in the book–Augustus Gloop, Violet Beauregard, Veruca Salt, and Mike Teavee–inspire Wonka and his creator, Roald Dahl, to an ecstasy of conscientious judgment. At the same time, Wonka is himself a captain of the childhood obesity industry, an owner of a massive sweatshop of non-union Oompa-Loompas, and a celebrant of treats, goodies, excess, and culinary delight! The moral miscalibration of the factory is creepier in the Gene Wilder movie than in the book, especially accompanied by Quentin Blake’s innocuous illustrations. But the harsh punishments of the “bad” children always make me a little nervous. In short, Roald Dahl seems never to have gotten around to that psychoanalysis he needed. But who has?

Or maybe it’s just that he’s so good at thinking like children do, in unbridled wishes and dark prophecies, in subterfuges, feints, and magical associations. Whatever his life-story, his imaginary tales are the best–he always knows when to show and when to tell, he’s very sure at the rudder. They’re entertainments of consummate craftsmanship and I don’t think it can be held against him that they speak both to children’s dreams and to their nightmares as well. A parent must get his own mind straight if he’s to help guide a child through Dahl’s moral quandaries: it’s good indeed to wait your turn, be grateful for what you get, etc., but the consequence of breaking these rules isn’t being sucked up a pipe or shrunk to 2 inches tall; it’s good to like the sweet taste of life, and there’s no real punishment for that either; and maturity is not avoidance of punishment, as the Taliban would have it, but doing what you yourself think is happy, just, and good.

But even if you’re not a vigilant interpreter of the tale, because you’re tired or you forgot or you yourself don’t know the answer or you don’t care (like Pierre), it really doesn’t matter, because Dahl’s protagonists are always centers of moral calm, a perfectly safe and inviting vehicle for a child to climb into for a journey into the rabbit hole.