Is “Ellis Island,” the titular novella in this story collection, the best thing written on the American dream since the Declaration of Independence?

In 1981, when this book came out, The New York Times’s Anatole Broyard said of Helprin, “Nothing is familiar in his stories: he is interested only in the fabulous, the borderline between perception and hallucination, knowing and wishing. His characters exist in a state of sweet anxiety.”

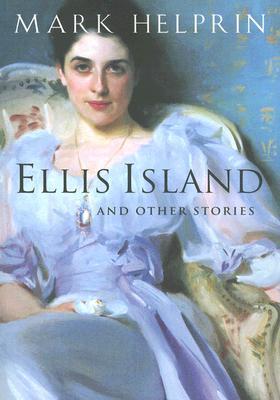

This romantic tension between dream and reality selects his subject matter, but also distinguishes his style. The cover of my edition is a painting of Lady Agnew of Lochnaw by John Singer Sargent, and Mark Helprin seems to paint his images in the mind with Sargent’s sumptuous colors and a similar blend of romance and realism.

And yet he differs from other practitioners of “magical realism,” such as that style’s founding father, Franz Kafka, or Kafka’s famous disciple Gabriel Garcia Marquez. For one thing, Helprin’s much funnier than Marquez. He can make me laugh out loud in 11 words; his rootless, rudderless narrator, fresh off the boat from Ellis Island, says, “No place would take me in, not even the Harvard Club.” There’s a lunacy to his humor that resembles Kafka’s, but Helprin is willing to dare something that Kafka wouldn’t: happiness.

Especially in “Ellis Island,” there’s a sense of joyous, wild abandon akin to that of a Jewish wedding, where for a moment everybody forgets every painful thing that has ever happened–to himself, to herself, to the Jews, and to all people–and drinks, and dances a sweaty dance of near perilous disorder, and hoists the bride and groom and even the parents of the bride and groom–people old enough to break a hip–onto teetering chairs, life-mates linked only by a betrothal white kerchief or table napkin as tenuous as hope, and supported on an unstable, moving buttress of generally unathletic, but surprisingly strong Jewish men in an improvised scrum.

Celebratory Jewish dance is in fact an image in “Ellis Island”:

The dancing was an engine, drawing light through the eyes of each soul into a cylinder of tightly bound rays that went up past the dome. I had heard of this in the East. They used to say that the great synagogues of Asia were like this. But I had never seen it. p. 184

And Helprin makes engines, trains, industry into emblems of joy, hope, humanistic power—who else dares to celebrate America in that way? How different from Edith Wharton’s America or Kurt Vonnegut’s. Mark Helprin sees America as a steam engine—or perhaps better to call it a dream engine—an engine casting off confusing clouds of vaporous dream, but also feeding on dreams to fuel the real work that makes dreams come true. And they do. “Everyone was in love with freedom,” Helprin writes, “and it is one abstract quality which, somehow or other, always manages to love you back.”

The tension of dreaming derives from the uncooperative, inhuman aspects of reality. Like skulls peering out between the happy letters A-M-E-R-I-C-A in “Ellis Island” are the ghost letters A-U-S-C-H-W-I-T-Z. The story seems to take place before 1940, but the cultural memory of Auschwitz has imprinted itself here. Helprin says that the immigrants at Ellis Island had to go upstairs to examination rooms.

They prayed as they went up. Even had we not had the sense of floating in Heaven, the idea of judgment was implicit in every angle of the place. Some had great difficulty struggling up the stairs, and at the top were led away to be sent back—since the doctors could easily see that their hearts were not strong enough for America. pp. 137-138

The narrator appears to interpolate or imagine this fatal sorting of weak and strong by doctors, but does the image not call to mind Josef Mengele and Nazi eugenics? On p. 141 the narrator states: “They made us take a shower.” No Jew can picture his ancestors in an en masse compulsory shower without thinking of Auschwitz and Zyklon B, and that will likely be true for the next ten thousand years. Finally, on p. 168, Helprin refers to “the morning industry of the city’s six million hands.” “Six million” too is an unmistakable symbol—the number of Jews who perished in the Holocaust.

By a trick of metaphor, Helprin’s America resurrects those six million dead, turns death showers into innocent ones, the nakedness of death into that of love and sex (an art teacher says, “America to you now is a big nude woman, and that’s just fine”), tombstones into towers of glittering glass. It isn’t perfect, it can’t bring the dead back, and in the end, the narrator must lay aside certain evasive dreams in favor of realities that include death, but the reality is that America has made many a dream come true for real, that it plays host to gigantic love, health, freedom, and industry, to all that grain out there in Nebraska, to many of the profoundest aspirations of men and women, conceived in the dream engine of the world and transformed with great labor into more complex, but still satisfying, realities.

The narrator of “Ellis Island,” a former rabbinic student with a literary bent, hides behind a variety of pseudonyms and ends up writing for the Jewish Daily Forward. He shares all these attributes, one notes, with the real writer Isaac Bashevis Singer, a master of that age-old dialectic between dream and reality. And so Helprin realizes his own dream, I think, of joining the ranks of his literary forefathers.