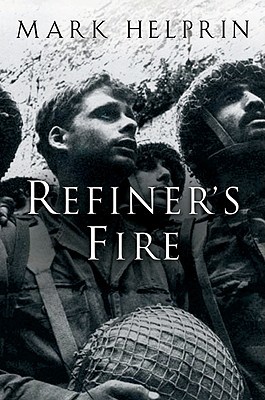

Refiner’s Fire was Mark Helprin’s first novel, published in 1977, a semi-autobiographical fantasy that follows Marshall Pearl from his childhood in the Hudson Valley through many adventures on the sea, in the mountains, and in the plains, in the classrooms of Harvard and finally in the Israeli army. A London newspaper described the book like this: “As if The Odyssey had been updated and rewritten by Dylan Thomas.” There is a sense in which that’s true. There’s another sense in which it’s as if some gifted poet had rewritten a trashy spy-novel or romance. Either way, it’s highly entertaining, engaging writing that’s at times aesthetically magnificent.

Mark Helprin is an interesting case. His website says, “Mark Helprin belongs to no literary school, movement, tendency, or trend. As many have observed [including, perhaps most often, himself (—A.R.)] and as Time Magazine has phrased it, ‘He lights his own way.’ ” In an American literary scene dominated by liberals, he’s an unapologetic conservative, a former speech writer for Bob Dole and an occasional columnist for the rightwing op-ed page of the Wall Street Journal. He once was published regularly in the New Yorker, but no longer, and he has expressed both frustration at the unprecedented level of corruption of literary art by commercial forces (somewhat iconoclastic for a conservative) and also the probably justified view that the literatti have expelled him because of his rightwing politics.

He is a self-styled maverick, but also an actual one. He believes in the art of truth and beauty in an age where cultural criticism has for many called Keats’s maxim, and aesthetics as a whole, into question. Helprin is attracted to heroic ideals as in ancient myths and epics, not because he wants to deconstruct those ideals but because he more or less subscribes to them, and because he thinks the heroic “paradigm of the romance,” as he calls it, “has been the preferred method of storytelling for human beings” since time immemorial–justification enough, perhaps, if what is old is good. In any case, his aesthetic achievements are often very great. His sentences spring to life. They overflow with sensation and a sense of the emotional and aesthetic importance of physical sensation, the meaning of sensation in the scope of a life history; places echo with the footsteps of forefathers, forests bend in the wind as if remembering the ancient enemies who trod there, etc. He’s masterful with hyperbole and magnifies real life with the awe of fathers, lineage, great deeds of the past, and great men, the fear of not measuring up, and the joy of victory. I admire his iconoclasm, and have been influenced as a writer by his wonderful effects.

At the same time, he doesn’t really “light his own way.” For one thing, he’s afflicted with a certain submissiveness before ideology. This has led him to take political positions that are to my mind bizarre, such as his view that the U.S.’s top 21st c. priority is to build up our navy vastly to counter China’s influence in the Pacific. (Uh, really? That is so last-century, it was actually last-century last century–an assessment to which he might not object since he wants to live like Perseus or King David.) And his ideology contaminates his work with a phony machismo, a warmongering and jingoism, and worst of all, an evasion of internal conflict. It’s as if in his reading of ancient texts he missed the parts about hubris as a tragic flaw, and guilt, and the curse of the house of Atreus, and the fear of the Furies. Beowulf has more internal conflict than Marshall Pearl.

Helprin said in an interview that in the 19th c., realism killed the “romance,” by which he means his particular idea of a heroic, epic quest-narrative. But his greatest talent is, ironically, for a unique brand of magical realism—for wonderful naturalistic descriptions imbued with a kind of simultaneous memory and anticipation, a realism that situates all experience within a larger curve of father-son relations, and injects all experience with an idealistic, heroic yearning drawn from those relations. He is a realist, and a very good one. If he only realized that, I think he could succeed in depicting the heroic ideal as a beautiful psychological force rather than fall victim to that ideal’s partly juvenile and ridiculous worldview. The tension of Marshall Pearl’s unfulfilled promise to his forefathers and his destiny winds up Helprin’s narrative in an entertaining, but ultimately not literary way. And Marshall Pearl’s epic journey consequently does not lead him to Valhalla, where Helprin wishes him to go, but instead to Hell, where he’s condemned to be a cartoon.

That said, Helprin is a writer of huge talent, and I love him for his love of truth and beauty, notwithstanding his circuitous efforts to find it, and, no matter how macho he pretends to be, I love him for the actual rugged individualism that dwells underneath. Most of all I love him for his sensitivity to the delicate affair of fathers and sons and the destinies they imagine for themselves and one another.