Hobbes reminds me, in a good way, of the ape who learned to act like a human being in Kafka’s hilarious short story, “A Report to an Academy.” The Kafka story begins:

Honored members of the Academy! You have done me the honor of inviting me to give your Academy an account of the life I formerly led as an ape. I regret that I cannot comply with your request to the extent you desire. It is now nearly five years since I was an ape, a short space of time, perhaps, according to your calendar, but an infinitely long time to gallop through at full speed, as I have done, more or less accompanied by excellent mentors, good advice, applause, orchestral music, and yet essentially alone….

Hobbes trains his attention on our primate nature, a nature prone to quarreling from three principal causes, as he sees it (p. 185, Penguin Classics ed.): Competition, Diffidence (i.e., fear), and Glory. And we are motivated in our quarrels accordingly, says Hobbes, by the objectives of Gain, Safety, and Reputation. I hear ya, brother, give me some of all that. He sure is preaching to the ape.

Many people think of Hobbes as a cynic with a low opinion of human beings. But that’s wrong. On the contrary, Hobbes is very sympathetic with us hungry beings in need of food, safety, and respect. He is far more sympathetic to innate Desire than St. Augustine, for example:

“But neither of us [Hobbes himself and the average man who locks his doors at night] accuse mans nature in it. The Desires, and other Passions of man, are in themselves no Sin. No more are the Actions, that proceed from those passions, till they know a law that forbids them….” (p. 187)

Another reviewer expresses hatred for Hobbes because of his supposed endorsement of the reign of Christendom. There is a late section in Leviathan on “Christian Common-Wealth,” and I confess I haven’t read very much of that part, but what I did read was nothing other than an attempt to compel people with Christian morals to see that the Bible does not invalidate or supercede his rationalist political and moral philosophy. In Part II, “Of Common-Wealth,” which I have read thoroughly, he makes it pretty clear what he thinks of religious claims to political authority (p. 230):

“And whereas some men have pretended for their disobedience to their Soveraign, a new Covenant, made, not with men, but with God; this also is unjust: for there is no Covenant with God…. But this pretence of Covenant with God, is so evident a lye, even in the pretenders own consciences, that it is not onely an act of an unjust, but also of a vile, and unmanly disposition.”

All righty then. His revolution was the systematic application of reason to the planning of society; he derived his conclusions from first principles of human passions that he didn’t intuit but observed, in others and also in himself–he exhorts us (p. 82), Nosce teipsum: Read thy self. Supposedly he knew Descartes and Galileo and was influenced by them; like them, he is one of those Leviathans of rationalist, humanist Renaissance thought who laid the groundwork for the Enlightenment. He was less imaginative than John Locke, it’s true, when it came to the possible forms of political representation, but it was he, before Locke, who described government as a social contract between men by which those men defend themselves from each other and from their own passions; it was Hobbes who described government as a representative of its citizens and not of God.

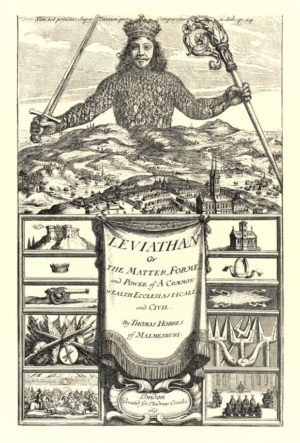

It’s impossible not to love the engraving on the cover of the Penguin Classics edition, which comes from the frontispiece of the original from 1651. Across the top it reads, “Non est potestas Super Terram quae Comparetur ei,” meaning “There is no power on earth which can be compared to him.” That’s a quote from Job about a “big, ugly monster” as my three-year-old would say. But Hobbes means something different: he means the monarch who embodies the interests and security not of God but of human beings.