Last week one of Newt Gingrich’s several wives told ABC news that in 1999 he asked her for an open marriage. Evidently, she didn’t possess the amphibian flexibility required for marriage to newts or salamanders, because she declined, and they divorced.

Newt Gingrich isn’t the first organism to propose an innovative mating arrangement. Banana slugs, for example, are hermaphrodites that prefer sex with another slug, but when times are dry or they’re very busy, they can self-fertilize, that is, literally “fuck themselves.” Perhaps Newt Gingrich ought to consider this.

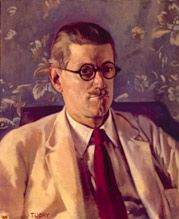

Of course, I mention Newt Gingrich only in part because of an interest in cold-blooded invertebrates. His affection for “open marriage” also calls to mind a question raised by the end of James Joyce’s Ulysses.

In Ulysses Molly Bloom cuckolds her husband Leopold with Blazes Boylan, a concert manager. Bloom knows about the affair, but when he lies down that night in the same space where Boylan lay with Molly earlier, he doesn’t confront his wife. She in turn suspects he gratified himself that day, which he did, having surreptitiously masturbated while looking at a girl at a seaside fireworks display. Bloom also conducts a flirtatious correspondence with another woman under the pen name Henry Flower.

But these extramarital activities don’t drive Leopold and Molly apart. Molly’s thoughts in the end return to Bloom and the day of their engagement, and Bloom is satisfied to lie in bed beside her the wrong way round, with her head at one end and his at the other, and in fact he kisses “the plump mellow yellow smellow melons of her rump.” I understood this wrong-way embrace to celebrate the imperfect, homely, and polymorphous realities over the sort of polarized conscience-driven ideals that Newt Gingrich inflicts on everything but his own banana. The realistic couple turned askew in bed specifically revises Homer’s mythic image of Odysseus returned to the bed of Penelope after years of wandering in Book XXIII of The Odyssey. As Odysseus himself pompously explains, he built his marital bed on the immovable stump of a big olive tree with its roots deep in the earth and used his conscientious carpenter’s tools to straighten the curved wood. (Read your Kant, Odie: “Out of the crooked timber of humanity no straight thing was ever made.”) Penelope in turn breathlessly reassures him that “no human being has ever seen [our bed] but you and I and a single maid servant.”

Molly is no waiting Penelope knitting a shroud for her father-in-law—and she’s better for it. But was Joyce really endorsing “open marriage,” and is that the best we can hope for? It still seems to me the least we mortals can expect from life is loyalty from ourselves and from each other, honest though we may be about the polymorphous infidelities in our hearts.

Two touching biographical details show the value Joyce placed on constancy in the marital bed, which is not only a place for sex but for love and caretaking: when Nora had surgery in 1928, he insisted that he sleep beside her in her hospital room. And when he was himself dying from a perforated duodenal ulcer in 1941, he asked that Nora come to sleep beside him. Alas, she couldn’t get there in time and he died alone. (Ellmann, James Joyce, pp. 607, 741)

In aspiring to write a “complete all-round” character like Odysseus, Joyce always touted Bloom’s status as family man. He told Frank Budgen that Jesus Christ was not so complete: “He was a bachelor and never lived with a woman. Surely living with a woman is one of the most difficult things a man has to do, and he never did it.” (Ellmann, p. 435)

Ulysses is an epithalamium (i.e., song in celebration of conjugal love) as Joyce biographer Ellmann says (p. 379), but one that aspires to fidelity in the context of relentless human desires, imperfections, anxieties, and even grief. It doesn’t depict an open marriage so much as it does an imperfect and real one torn by grief and anxiety and convalescing towards closure. While the text buries references to the Blooms’ despair—like Molly’s glancing thought “our 1st death too it was we were never the same since”—it provides indisputable evidence of grief’s influence on their marriage.

In the penultimate “Ithaca” chapter, structured in questions and answers like a catechism, Joyce writes that Molly and Leopold did not have “complete carnal intercourse” for a period of 10 years, 5 months, and 18 days. It also says they last had “complete carnal intercourse” on November 27 1893—while Molly was pregnant with their first child. Their son Rudy was born shortly after and then died at 11 days old. Don Gifford’s Ulysses Annotated instructs that the ten year fallow period is an allusion to the ten years Odysseus spent wandering apart from his wife after the fall of Troy, and to the beginning of Canto XXXII of Dante’s Purgatorio, where Dante says he hasn’t seen Beatrice in ten years. But more importantly, if you add 10 years 5 months and 18 days to November 27 1893, you find that Molly and Leopold broke their fallow streak on May 14, 1904, about a month before the day on which the novel’s action takes place. It suggests that the adultery belonged to a troubled, grief-stricken period that is drawing to a close rather than to Molly and Leopold’s future. And this makes Molly’s climactic reaffirmation of her marital vows yes I will yes all the more meaningful.

I have the sense that Joyce’s high reputation is partly based on the admiration of those who don’t really appreciate what’s great about him, but only assume anything so confusing must be profound. His profundity lies not in his abstruseness but in his naturalism, his parody of primitive myth, and his insistence that even in so imperfect a world, the center can hold, and not everything falls apart. Joyce was imperfect, for sure, but he was no amphibian.